Just one week into the ESPN series, The Last Dance, chronicling the rise and fall of one of the greatest championship runs in the history of sports, it was clear who would play The Villian: Jerry Krause. Conveniently, everyone who is left to play pin-the-tail-on-the-scapegoat has chosen the dead guy. But perhaps it was Jerry, himself, who wrote his own role when he let slip the fateful line to a reporter at the height of Bulls dominance, “Organizations win championships.” He claims he prefaced the remark by saying “Players alone, don’t win championships.” Nonetheless, he said it.

Immediately, everyone claimed Machiavellian motivations to the quote. Even Michael Jordan himself — in his Hall of Fame address no less — still holds it against him. But this was simply a leader of an organization, saying what he knew to be true: that there were hundreds, if not thousands, of people in the Chicago Bulls orbit that deserved just a little smidge of credit when the Gods of Fate retold this mythical tale of Victory to the masses of History.

Perhaps Jerry should have been more careful with his words and known that the greatest sin in any organization is just this: Stating the The Truth. Plainly and simply. The truth shall set you free. That’s because, as soon as you utter it, you’ll quickly be left standing all on your own. Nobody likes to hear the Truth. Least of all, the player known as The Greatest Of All Time. Piercing the myth and mass delusion of Air Jordan — even slightly — built up by billions of dollars of TV broadcast rights, millions of shoe sales, and thousands of magical commercials, simply guaranteed the wrath of legions of fans as well as the entire NBA league.

But anyone who’s ever spent more than a few years in any size team, organization, company, industry—any decent size group of any kind — knows this is true. And it’s especially true in especially high-achieving and high-pressure groups. Organizations win Championships. It’s simply true on the face of it. How could it not be? If great things could be accomplished by one person or even one tiny group of people — why would we just tack on the additional hundreds and thousands of extra people and why create these elaborate, fine-tuned systems of checks and balances, rewards and punishments, rules and regulations, if we didn’t have to?

Any kid who’s ever played on any team – even just peewee soccer or park district Little League — learns this at a young age: success is simply a result of getting a group of people to compete and cooperate at the same time. It’s simple, but it’s not easy. And to achieve at the highest level, any organization must manage vicious competition while also encouraging vigorous cooperation. Managing that dynamic is incredibly hard and incredibly complex. And nowhere is that more obvious than the greatest basketball team of all time, the 1990s Chicago Bulls.

Watching the Bulls in the 90’s as a high school kid in Chicagoland was to be enchanted by excellence. We simply expected the extraordinary, year after year, without fail. And without compromise. I was old enough to have suffered through the 84’ Cubs and the 86’ Bears to know that this run was special and not at all ordinary. But I was young enough to have no real clue how it actually happened — what real sacrifices were made and what toll it took on the players and the team. Sure, there was plenty of press and leaks and rumors from Sam Smith and others —especially when Jordan suddenly up and went AWOL in ’94. But we saw it all through the eyes of Optimism and the lens of Myth. So watching the Last Dance now, 20 years later, and getting a glance at the real story, however slight, is enlightening.

The undisputed Hero of this tale — no surprise as he has Final Cut and Final Say — is perhaps the most competitive person ever to walk the face of the Earth: Jordan. Without question, he was a hero. A Superhero. His skill and talent was visceral, poetic, grandiose like no athlete before. I didn’t get to watch Babe Ruth or Mohammad Ali in their time, but I’m confident they never radiated awe quite like Michael Jordan. As a fan, seeing Jordan down or behind in the clutch was quite literally like watching a Bull see Red. He would get blood in his eyes, steam in his nostrils, and turn ballistic. Tongue hanging, head shaking, he would enter a zone only he could enter. Just like any other Superhero, he would undergo an uncontrollable transformation in order to assume complete control of any situation. That’s the Mythical Giant we all bought into. But Jerry had to deal with reality. And reality meant buying-in, and building up, a team.

Jordan alone would never– could never–win a Championship. He knew it. The Bulls knew it. The fans knew it. The moment he stepped on the court, the entire NBA knew it. Here was a guy who could score half his team’s points, every night, and still lose. The only question about Jordan was not whether he could become the Greatest Player of All Time, but whether he could ever get out of his own way. Whether he was so competitive and so dominant that he would not only destroy everyone else, but himself, in the process. Somehow, Jerry Krause recognized this epic, tragic flaw in our Hero early on.

That’s because, above all, Krause was a Scout. He had an incredible eye for raw talent and understood the true makeup of an individual, both physical and psychological, like only a great scout can. Krause did not draft Jordan. But anyone sitting at number three with Jordan on the board would have drafted him. More importantly, Krause knew exactly what he had inherited in Jordan– instinctually and immediately. Sure, benching Jordan in Year Two long after his injury had apparently subsided and holding back the Bulls to try to make the Lottery was ruthless. It was a gangster move. It violates an unwritten rule of competitive sports that you should never give up. But according to the game theory of organizational dynamics: was it wrong? The Bulls were not going to win that year, or any year, if they did not build a team.

The Celtics of the 80’s were dominant. And while Larry Bird and the rest of the team was too humble to say it, the strategy of that series was clear: Rope-a-dope. Jordan would charge ahead. He’d come out swinging. And he’d exhaust himself and everyone else in the process. Jordan threw down 63 points, a playoff record, sent the game into overtime, and the Bulls still lost –that game, and every game, that series.

Right or wrong, by now, the organizational strategy of “tanking” when you’re in a rebuilding phrase is just a common, accepted practice of every major sports franchise in every league. In fact, it’s a practice of every major Fortune 500 company that ever had a really bad quarter in order that they could string together years of un-interrupted earnings growth. But it wasn’t an accepted practice back then. It just wasn’t done. At least, not explicitly. Was Krause’s transgression as an operator simply that he was competing too aggressively? He recognized too early on the tactics that would eventually be embraced by every GM given the byzantine rules and regulations governing the leagues. And, once again, his fatal flaw was that he was perhaps too obvious about what he was doing. He was no politician. He was a tactician.

That episode is the clearest and most damning Act in the anti-Krause story arc. But even that supposed evidence of Villianry relies on an entirely uncharitable interpretation of the facts. There is also the much more reasonable explanation that Krause was simply being incredibly protective of the organization. He saw a massive risk in the injury of the greatest star and very little reward in exposing the entire future of the team for one unproductive playoff run, so he managed that risk / reward to maximize the long-term benefit to the team. Jordan would play, but he would cap his minutes. He’d hold back a charging Bull for his own good. This, too, is now common accepted practice among every other professional sports organization. With injuries, especially to young stars who don’t understand Risk and only see Reward–err on the side of caution. As Chicago fans, we know too well what happened when other organizations risked their star players for short term gains, like Kerry Wood on the Cubs or Wilbur Marshall on the Bears. You can win some games, or even a season, by being reckless and risky. But you can only create dynasties by ruthlessly avoiding risk.

The stark reality for any manager is that any organization has finite resources. And naturally, the talent of any organization will compete, brutally, for those rewards. It’s a dangerous fantasy for any manager to assume that everyone can get everything they want and that everyone will just get along. In any group, some sense of hierarchy must be established to measure out individual recognition in line with the level of contribution of an individual and the overall achievement of the group at large. If this hierarchy is not carefully balanced and significantly fine-grained and fine-tuned to encourage the right amount of competition and cooperation among the participants, what typically happens is that nobody gets what they want, and nobody gets along.

In the NBA, the Salary Cap–limiting the payroll of any team to a hard, overall cap–means that any one player is competing directly with every other player on the team to get a bigger slice of financial recognition. The overall pie is finite. So if you want to build a better overall team, everyone needs to cooperate. There has never been a more shrewd operator of payroll with a more nuanced understanding of the legal and emotional implications of it than Jerry Krause and his team. Eventually, they would even be sued by the NBA for finding a hire / fire / re-hire work-around of the salary cap to land Toni Kukoc and properly compensate him. They would win the lawsuit. And the league would have to rewrite the rules. That’s how deftly Krause danced on the edge of the line when the Bulls were at their peak.

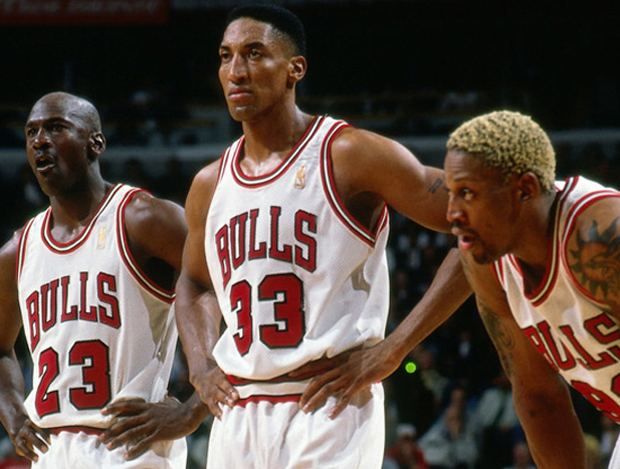

Episode Two of the Last Dance zeros in on Scottie Pippen feeling underpaid and underappreciated in 1997, the last year of a very long contract. But it underplays what a defining move it was for Krause and the Bulls organization to trade up in the draft to select the obscure player from Central Arkansas, “Scott” Pippen, in the first place. Whether a stroke of genius or just dumb luck — Krause was clearly focused on a singular task of building the right people around Jordan. And he knew instinctually that the ultimate Competitor would require the ultimate Cooperator. Small-town and small-school Scottie Pippen was as humble as raw talent can get. It’s fair to say that Jordan would never put up with anyone who challenged his dominance on and off the court. And it’s fair to say that nobody but Pippen would put up with Jordan taking so much of the spotlight while he put up so many numbers himself.

Signing Pippen to a long-term deal gave Scottie the security and recognition he craved at the time and it gave the Bulls the perfect complement to Jordan with which to build the team. Sure, the contract looked cheap after Year Eight and Championship Five, but hindsight is 20/20. Back when Jordan made 4 mil, Pippen made 3 mil. In any organization, recognition is relative. Krause knew early on, he had to find a way to keep a lid on the kettle and balance every player’s competitive spirit with every other player or the whole thing would boil over. Scottie Pippen was that perfect, steady No. 2 that every organization desperately needs.

Anyone else joining the team knew there was no daylight to exploit between Pippen and Jordan. They would have to fall in line. When Krause entertained a trade of Pippen for Shawn Kemp straight-up, he might have found the only player in the league who could improve on Pippen’s numbers, but he knew there was little chance he could improve on Pippen’s chemistry. The deal fell apart. From then on, the list of role players and specialists that were brought in at every turn in the dynasty, exactly when they were needed, is simply too long to mention in detail. Cartwright, Paxson, Grant, in the first wave. Kukoc, Kerr, Rodman in the second wave. It makes for a masterclass in managerial excellence. If everyone knows their role, they will feel gratitude when they fulfill it; not resentment when they don’t. Sure– Phil Jackson had a lot to do with this as we will no doubt see in the next episodes of the series. Much more than Krause did. But Krause had a lot to do with Phil Jackson, plucking him from the CBA and giving him a long leash for an unorthodox, player-first style that was not natural to Krause. Give him some credit for recognizing his own deficiency and finding a Coach who could compensate.

The one charitable tidbit toward Krause in The Last Dance was giving him credit for recognizing the genius of Tex Winter’s “Triangle Offense” and insisting the Bulls run it. This was a brief, passing mention. In reality, Krause had to make a huge sacrifice to move forward with his vision for the team. He had to fire Doug Collins – the first Coach that got the Bulls to the playoffs – at the pinnacle of his success. Not only that, he chose to install the completely unproven Phil Jackson who he knew would embrace the (highly experimental) Triangle Offense that had the crazy plan of taking the ball out of the hands of their star player and force him to actually pass the rock once in awhile. This was as gutsy a call as any General Manager has ever had to make. Krause bore the brunt of the move while Jackson got all the credit for the success of it. Thanks in part to the Triangle, Phil Jackson would eventually be turned into an international sensation as a cult-like Guru of creative management, while in reality, Jackson had the least to do with actually enacting the underlying system. That’s not to diminish Jackson’s clearly exceptional talent for coaching and getting his players to perform. But perhaps it lends some sympathy to Krause’s resentment toward Jackson at the end of the line. Did Jackson ever publicly thank Jerry for his early, absolute faith in him and giving him his shot? Not that I’m aware of. Instead, Jackson allowed – and even seemed to encourage – the open mocking of Krause by Jordan and the players. Which grew into such a malignant cancer on the team that Pippen, the softest spoken teammate, felt justified in berating Krause on the team bus, sat-out during a final play in the playoffs, and eventually, sat out most of the final season of his contract. If Jackson deserves the praise for a loosey-goosey style of management that allowed player’s competitive spirit to flourish, he also bears some responsibility when that same approach breeds resentment and feeds player’s sense of entitlement to the point it erodes cooperation and poisons the team spirit.

The Last Dance focuses on why the Bulls were never allowed to make a run for Championship Number Seven, but watching in hindsight — it’s a wonder they even made it past Number Three. When Jordan finally made it to the end of his contract, he demanded to be paid more money than any athlete in any sport, ever. Did he deserve it? Sure. But did he need it? Once the salary cap was skirted once for one player, you can’t put the lid back on the pot.

Part of the genius of Krause and the Bulls organization was letting Jordan gain vast rewards and recognition outside of his contract and outside of the team. While they didn’t create the phenomenon of celebrity endorsement deals, they didn’t get in the way. And unlike the ’85 Bears, they didn’t let it corrupt the team. Jordan was allowed to become, not just a celebrity, but an international sensation–a white dwarf of a star that burned brighter than anyone else. And his ego was just as enormous.

We’ll never know the true depths of Jordan’s competitive destruction in the form of his gambling habit, the death of his demanding father, and why he felt he needed to compete in a whole other Sport and waste away his talent in Double A in ’94. But the point is — The Bulls organization knew better than to try and contain it or shut it down. They were patient to a fault. In fact, they enabled his diversion, as Jerry Reinsdorf owned the White Sox and gave him the chance to play baseball. Maybe they even coddled him. Whatever the correct word is — they didn’t get in his way — they skillfully managed his exit and skillfully managed his return. And all the while, they had to make alternative plans for the team – like signing Kukoc – at the same time Jordan effectively held the team hostage to his whims, not knowing if he would come back or when. And in ’96, Jordan used that organizational leniency against them.

Since the Knick’s owners also owned hotels and other businesses, Jordan’s agent, David Falk negotiated sponsorship deals as well as salary into a competing offer in order to force the Bulls hand into giving him 30 million a year. And then, next year, they did it again. Jordan could have accepted less under the cap. He didn’t have to paint himself into a corner that he would only play for Phil Jackson and nobody else. He could have left something on the table under the salary cap for Pippen or other players. But that’s not what ultra-competitive people do. It’s not enough to have enough. It’s only enough to have more than anyone else. And that’s why the Bulls ended up with Six Championships and not Five. One more than Magic Johnson’s Lakers. But it’s also the main reason they never ended up with Seven. All recognition is all relative. And when the reward is no longer there for top talent, neither is the drive.

As each episode of the Last Dance lionizes each member of that Bulls team, it’s certain that we’ll never get the same treatment for the general manager. There will be no adorable, sepia-tinged childhood photos of Jerry Krause or sympathetic, endearing quotes from his parents like we’ll see for all the players and coaches. Krause will continue to be portrayed as a squinty, shifty little dwarf of a man in a world of mythical giants. And maybe there’s some truth to that. It seems obvious that he wasn’t all that well-liked. But he also didn’t seem to mind. In fact, if he took the rap for the ill will on the team, maybe it meant he could deflect some animosity from Jordan or Jackson that surely existed and maybe that meant the amazing run would stretch on one more year. He might be saying, from the grave, go ahead and scapegoat me. Without a doubt, as each subsequent episode reveals each new piece of the puzzle, the documentary will only prove the obvious:

Organizations Win Championships.